Zaza Diaspora - A Conversation on the Zaza Identity in Europe with Faruk İremet

By Tsovinar Kirakosian

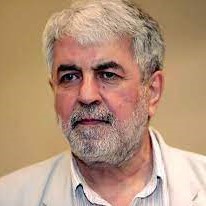

The Zaza diaspora holds a unique place within the migration movements in Europe. Zazas, who began arriving in Europe during the Ottoman period for various reasons, solidified their presence particularly after the 1960s through labor migration and post-1980 political migration waves. However, the process of recognition and preservation of their identity has not been easy. In this interview, we had an extensive conversation with journalist and writer Faruk İremet about the Zaza identity in Europe, the social structure of the diaspora, the preservation of the language, and the trajectory of the cultural struggle.

Tsovinar Kirakosian (T.K): When did the first wave of migrants arrive in Europe? Could Zazas have been among them, either as refugees in the 1980s or earlier, particularly when Turks and Kurds came to Europe as guest workers? Have there been specific waves or major migration flows since the 1980s (for example, after 2016)?

Faruk İremet (F.İ): The first arrival of Zazas in Europe dates back to the Ottoman period when they came to the Balkans as soldiers. Based on some identified information, we can say that some Zazas settled in Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Croatia, and even Sarajevo. Some of these settlements have been personally witnessed. For example, similarities in the names of certain foods and kitchen utensils suggest this. If we go further back in history, the presence of Zazas in Europe can be traced back to the Zazani (Sasanian) Empire. However, I will try to answer your question focusing on the more recent period, as you mentioned. After World War II, Zazas came to Europe, primarily to Germany, as laborers in the 1960s. A significant portion of these migrants were villagers from Siverek and Çermik, as far as I know. This migration occurred parallel to that of Turks and Kurds. Like Zazas, Kurds and Turks were also unemployed villagers from Anatolia. However, after the 1970 and 1980 military coups, a large wave of Zazas, especially from Dersim, migrated to Europe for political reasons. Most of those who left the country during this period were leftists, social democrats, artists, and writers. Besides Dersim, Zazas from Siverek, Çermik, Diyarbakır, Bingöl, Piran, Maden, Palu, Ergani, Hani, Sason, Varto, Sivas, Erzincan, and many other Zaza regions came to various European countries as political refugees. Almost all of them were either affiliated with the Kurdish or Turkish leftist movements. We also personally witnessed some Zazas from major Turkish cities like Elazığ, who were members of right-wing Turkish organizations, joining this political migration.

T.K: Which countries did they migrate to? Do you have any information about the demographics of Zazas (beyond Germany and Sweden, and within these countries)? Are they included in the demographic statistics of any EU member state (or are they listed as Turks or Kurds, and is their identity recognized as a separate community from Turks and Kurds)? Were they, and are they still, considered Turks or even Kurds by host countries because they are Turkish citizens?

F.İ: In recent years, love marriages have also contributed to this migration wave, and Zazas have started migrating to Europe again as part of the labor force, and this migration continues. While the primary destination of the initial migration wave was Germany, and from there, Zazas spread to other countries, there are still Zazas migrating to other European and Scandinavian countries. I do not have statistical information on how Zazas are recorded in the demographic statistics of EU member states. However, regarding Sweden, due to my long-term role there, I have some information. For example, in Sweden, Zazas and other ethnic groups or minorities from Turkey are registered as „Turkish citizens.“ However, their ethnic identity, native language, and religion are also recorded. Recently, Kurds have broken this taboo.

T.K: Did European countries provide a foundation for the formation and development of the Zaza identity from the moment they arrived?

F.İ: Zazas have not only been subjected to assimilation efforts in Turkey but also in Europe, where they have often been subsumed under a dominant identity, either Turkish or Kurdish. The struggle for Zaza identity is a recent development, emerging over the last forty years as a result of a costly struggle. Zazas have consistently been targeted by Kurdish nationalist factions due to their demands for recognition as a separate people and identity, and they have often faced violence. If Zazas today can assert their ethnic identity in European state institutions, it is the result of a determined struggle. In Germany, France, and Sweden, our friends have fought hard to officially recognize the distinct ethnic identity of Zazas. In short, this right was not handed to Zazas on a silver platter.

T.K: How homogeneous and united is the Zaza community in Europe? How does the community differ from country to country? Is there competition among Zazas in different European states or within the community in a single state? An additional question: What are the occupations of Zazas in European countries?

F.İ: Zazas in Europe have been tirelessly working towards unity and solidarity for a long time, and they have finally laid the foundations for cooperation. Currently, there is a strong effort among Zazas of different sects and political affiliations to unite on the basis of brotherhood and solidarity. This effort has been ongoing since Ebubekir Pamukçu initiated the Zaza national identity struggle in 1984. We are a community that rejects political and sectarian differences and unites around the common goal of Zaza national identity. We have prioritized intellectual accumulation, traditional organization, and embracing the Zaza national identity, and we have succeeded. Zazas are a homogeneous group, but political and sectarian differences are natural. These differences have been transformed into a richness through the efforts of sensitive Zaza intellectuals, media outlets, associations, and the legal political party of Zazas in Turkey, the Democracy Time Party (DEZAP). DEZAP’s chairman, Dilaver Eren, has made significant contributions in this regard. Zazas in Europe are engaged in various professions and jobs. Among them are those who have opened their own businesses, artists, academics, and a large workforce. Our -60 generation consists of exiles from the September 12, 1980 military coup. The September 12 events brought a significant number of intellectuals, academics, and educated individuals to Europe. This generation is now heavily involved in state institutions in Europe. For example, I myself have been working as a civil servant in various state positions for 22 years, and I am not alone in this.

T.K: When did Zazas start acquiring citizenship in host countries, or have they started at all? Have Zazas integrated into the host country (first, second, and perhaps third generation)? Or have they been assimilated?

F.İ: I will answer these two questions with a single response. Zazas integrated more quickly into the new societies they joined in Europe compared to many other ethnic groups. Why? Because every Zaza individual who came to Europe was at least trilingual or quadrilingual. This was the fastest key to learning the language of their new country and integrating quickly. As a result, the doors to employment and education were wide open for them. For example, a friend of mine who had not completed primary school, despite being over 30 years old, graduated from Stockholm University’s program department and became a computer teacher in high school. I have many similar examples. Zazas have integrated rather than assimilated.

T.K: Are there marriages between Zazas and Turks, or Zazas and Kurds, or with citizens of the host country? How do Zazas in Europe interact with Kurds and Turks in Europe?

F.İ: There are marriages between Zazas, Turks, Kurds, and citizens of the host countries. Especially before the September 12 military coup, the revolutionary struggle influenced Zazas, Turks, and Kurds alike. This is common among intellectuals, leftists, and academics. Zazas traditionally did not like to marry into the nations we consider old, to avoid assimilation and to protect their lands. Historically, the involvement of these two nations in massacres against Zazas has hindered marriages. In Europe, however, the situation is different. A Zaza who willingly adapts to that life also looks at marriage from an integration perspective. I am one of those people. I have been married to a Swedish woman for 23 years, and we have a 16-year-old son. This marriage has not kept me away from modern Zaza literature; on the contrary, I have taken the lead in it. My wife even speaks Zaza.

T.K: Which generation (first/second) knows the Zaza language better? Which language is used in the daily life of Zaza communities in Europe (Turkish, Kurdish, Zaza, or the European language)? What schools do Zaza children attend (Turkish, host country)? Are there schools where Zaza is taught as an elective? Do they have the right to education in their mother tongue? Is there a standard Zaza language? Are they pursuing higher education?

F.İ: Of course, the first generation knows the Zaza language best. If the first generation does not know their mother tongue, they cannot teach it to the second and third generations. The first generation in Germany is quite sensitive about the language and uses Zaza daily. The second language, naturally, is the official language of the host country, used in daily life. Work, legal procedures, social interactions, and school life are conducted in the language of the host country. Children, of course, continue their education in the schools of the host country in the host country’s language. The second generation of Zazas is also successful. Zaza mother tongue education was first officially recognized in Sweden in 1994, and Zaza writer Koyo Berz is the first official Zaza language teacher. There is no standard Zaza language yet. Such an imposition, being artificial, would create division rather than unity. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize the use of Zaza dialects in common journals and platforms, allowing each Zaza to write and use their own dialect. In other words, the ear should absorb different dialects. A standard language is a necessary but early step for Zaza, and it will undoubtedly be achieved by a committee of academics, linguists, and writers.

T.K: Were the first books, magazines, newspapers, TV channels, and publishing houses related to Zaza and Zazas published in the host countries of Europe (which ones and when)? Or was there Zaza publishing in Turkey before the first migrants came to Europe? What is the situation now?

F.İ: The history of written Zaza texts dates back to the 1700s. These were mostly religious works written in the Arabic alphabet. It is worth mentioning two examples of the first printed books containing Zaza: The first Zaza texts written in the Latin alphabet were compiled by the Russian scientist Peter Lerch from Zaza-origin Ottoman soldiers captured during the Crimean War (1853) and published in Petersburg in 1857-1858. The Zaza poet Ahmed-i Xasi’s book „Mewlid-i Nebi,“ written in Zaza in the Arabic alphabet, was printed in Diyarbekir in 1899.

In the modern era (since 1963), the first written Zaza texts in Latin letters in Turkey were poems, tales, stories, and fables published in some Kurdish magazines. Ebubekir Pamukçu’s Zaza-Turkish magazine Ayre, published in Sweden in 1985, with the statement „Zaza is a separate language and Zazas are a separate people,“ and later his magazine Piya in 1988, initiated a national mobilization among Zazas. In line with this view, many Zaza-Turkish and some in 3-4 languages, magazines such as Zerqê Ewroy and Waxt in Germany in 1990, Raya Zazaistani in Sweden in 1991, Raştiye in France in 1991, Desmala Sure in the UK in 1991, and Ware in Germany in 1992 were published successively. Later, the first entirely Zaza magazine, Kormışkan Bülten, published in Sweden in 1995, embraced all Zazas and initiated the first milestone of Zazas. As Faruk İremet, I was the chief editor of this magazine, and writer Koyo Berz was the official owner. Following Kormışkan Bülten, a new entirely Zaza magazine, Tija Sodıri, started its publication life in Germany in 1995. Then, in 2000, I launched a magazine called ZazaPress in Sweden, which continued for three years. I was the owner and chief editor of the magazine. Zaza writing life has achieved the success of publishing many books in 40 years through determined efforts. İremet Publications in Sweden, Tij Publications in Istanbul, Zaza Culture Publications in Ankara, and recently Vir Publications in Turkey have led the publication of many books about Zazas. Recently, Faruk İremet’s „Antolojiyê Nuştoxandê Zazayan / Zaza Writers Anthology,“ published by İremet Publications, was published in two languages (Zaza-Turkish) in June 2022. The book includes biographical information of 47 Zaza writers. This book is a document showing how rich Zaza written literature has become. Regarding TV, Zaza TV started broadcasting via satellite in Istanbul in 2022. This is almost the milestone of Zaza visual broadcasting. Meanwhile, individual broadcasts are also made over the internet. All these works are very valuable to us and should not be underestimated. I should also add: As a result of the determined struggle of Zaza intellectuals and writers to defend and keep the Zaza national identity on the agenda for years, Zaza „elective courses“ started to be taught in primary and secondary schools in Turkey by the Ministry of National Education as of 2010. Additionally, undergraduate programs in „Zaza Language and Literature“ have been opened at Bingöl University and Munzur University in Dersim (Tunceli), where Master’s and Ph.D. education is also provided.

T.K: Does religion affect the perception of ethnic identity among Zazas in Europe? Are there Cemevi (Alevi places of worship)? Do they practice their religion there? What about Sunni Zazas? Their identity? Do they go to mosques with Sunni Turks and Kurds?

F.İ: There are two sects among Zazas, namely Alevism and Sunnism. This issue has never been an obstacle among Zaza intellectuals and patriots. We Zazas in Sweden have not hesitated to provide all kinds of support to our Alevi friends to open Cemevi in different cities. The associations and Cemevi we have helped are still operating in Stockholm and Uppsala. As for Sunni Zazas, they perform their worship individually at home or in mosques, as well as collectively in mosques with different nations from different countries. Because mosques, like Cemevi, are common places of worship and do not make any ethnic distinction among Sunni Muslims.

T.K: The name issue - Do Zazas have their own names and surnames (names approved by the Turkish state can be used, officially used by all citizens who are not recognized as an ethnic-religious minority).

F.İ: The Surname Law in Turkey was adopted on June 21, 1934, published in the Official Gazette on July 2, 1934, and entered into force on January 2, 1935. The surnames of minorities (indigenous people) derived from their language were replaced with a Turkish surname, and this was even implemented arbitrarily by some officials based on their professions. Some of the indigenous people who came to Europe used the democratic rights given by Europe to change their surnames and transfer their old surnames to the European population. Turkey’s Surname Law was applied not only to the indigenous people but also to all immigrants from the Balkans. In fact, this can also be called a shame, assimilation, and „Turkification“ law.

T.K: How many Zaza associations are there in Europe? In which countries are they located? What do they focus on (social issues, political issues, identity issues)?

F.İ: We do not have exact statistical information on how many Zaza associations there are in Europe. Zaza associations are primarily in Germany, followed by the UK, the Netherlands, France, and Sweden. These associations work on Zaza national identity issues. Just placing the word Zaza at the beginning of an association or an article is now perceived as a political identity determination. And using the name Zaza is now a symbol of a political stance. On the other hand, as in many European countries, in recent years, in some major cities of Turkey (Istanbul, Adana, Mersin, etc.) and in many provinces and districts in the Zaza geography (Diyarbakır, Bingöl, Elazığ, Siverek, Gerger, etc.), associations operating in the fields of language, history, culture, and art with the name „Zaza“ have been established.

T.K: Have they organized any protests/lobbying/petitions (local/national/supranational level) to draw the attention of the public and policymakers in the host countries to any problems in the homeland?

F.İ: Zazas in their host countries use all democratic and bureaucratic channels to explain the existence of Zazas and that Zaza is an independent language, not a dialect of another language. Our friends from Dersim are working intensively to voice the difficulties faced by the Zaza mother tongue and the Alevi sect in both academic and bureaucratic channels. In this regard, the intensive work of DEZAP (Democracy Time Party) Chairman Dilaver Eren in Turkey should not be forgotten.

T.K: Is there Zaza nationalism today? Is there a legacy left by E. Pamukçu among Zazas in Europe?

F.İ: Although the term „Zaza nationalism“ was not consciously chosen, defending the Zaza ethnic identity, that Zaza is a language in its own right, with its own dialects and accents, is considered „separatism“ by Kurdish and Turkish nationalists who do not recognize the existence of the Zaza ethnic identity, and we Zazas are accused of being „Zaza nationalists.“ Years ago, I wrote an article and said: „I am a Zaza nationalist, from a single hair of my head to the nail I cut.“

If nationalism is the denial of other peoples, it is racism, and I reject racism as you do.

The struggle of oppressed peoples to defend their identity is not racism, it is the demand for their national rights.

Our nationalism does not deny the ethnic identity, language, rights, and laws of other peoples; on the contrary, it is based on defending the ethnic identity, language, rights, and laws of other peoples.

T.K: How has the freezing of Turkey’s EU membership and general relations with the EU and host countries affected the Zaza issue in Europe and Turkey?

F.İ: Europe has missed historical democratic opportunities several times. These historical opportunities were Turkey’s EU membership. Turkey’s EU membership would have opened the way for the democracy struggle in Turkey more. Some countries within the EU were able to become EU members without implementing democratic reforms. Reforms were implemented after membership. Turkey’s EU membership is in the interest of the indigenous peoples living in Turkey. One of these so-called minorities is the Zazas. I have great faith that with Turkey’s EU membership, we will achieve our democratic rights more quickly. However, I believe that the EU has deliberately sabotaged this democratization process. So who won? The extreme nationalist right-wing in Turkey won. This right-wing nationalist faction, as I wrote in an article years ago; „Turkey will become the new Iran at this rate!“ I guess we will be there at this rate.

T.K: How does Turkey react to the development of the Zaza issue in Europe?

F.İ: I do not have the courage to comment on this issue as we do not have information, documents, or documentation.

T.K: Have Zazas participated in any political movements organized by Kurds in Europe?

F.İ: Zazas have participated in many Turkish organizations and parties. That is, they have held leadership positions in both right and left groups and organizations. From the 1960s to the present, they have also played a role in the Kurdish movement, and this role was mostly leadership. For example, the former Co-Chair of the HDP in Turkey, Selahattin Demirtaş, is a Sunni Zaza from Elazığ/Palu. The Chairman of the CHP, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, is an Alevi Zaza from Dersim. The founding Chairman of HÜDA-PAR (Free Cause Party) and currently Deputy Chairman, Hüseyin Yılmaz, is a Sunni Zaza from Diyarbakır/Hani. The current Vice President of Turkey, Cevdet Yılmaz, is a Sunni Zaza from Bingöl. The leadership I mentioned is of this kind.

T.K: Are there Zazas in the politics of the host country? If yes, do they bring Zaza issues to the agenda? In which countries?

F.İ: Zazas in their host countries have taken part in both parliaments and political parties. There is intense political activity in Germany and Sweden. These members of parliament bring up the issues of Zazas in every field they are in, despite threats. The Zaza reality will inevitably be on the agenda as an undeniable fact.

T.K: Are there Zazas in the academia of the host country? Are they interested in identity issues in the EU and Turkey? Are there seminars and conferences on Zaza issues in host countries?

F.İ: I have already answered this question above. There is intense academic activity among Zazas, and academic Zazas are making great efforts to voice the Zaza reality and turn the agenda in favor of Zazas in every field. This is an honor for us. As I mentioned above, symposiums on the language, history, and culture of Zazas are occasionally organized at Bingöl and Munzur Universities, and many academics, both Zaza and non-Zaza, participate in these events with scientific papers on Zazas. Additionally, the mentioned papers/presentations are published as books by the mentioned universities and distributed.

T.K: Is there any financial support from Zazas in Europe to Zazas in the homeland for any political or cultural initiative?

F.İ: Of course, there is support from Zazas in Europe to Zazas in the country. Especially in the field of press and publishing, great help is provided. The aim is for Zaza to have a written history and to contribute to history with literature. This support started with the establishment of newspapers, magazines, and publishing houses. Magazines and books published in Europe were distributed without any return. In my opinion, this is a great support.

I thank you with the wish that this interview will benefit both you and the Zaza media. With my respects.

Tsovinar Kirakosian

Editor, Iran and the Caucasus, Brill: Leiden-Boston;

Researcher & Lecturer, Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian-Armenian University

02.07.2023

Zazaki.de

Zazaki.de